Market Commentary

2025 Outlook Part Deux

The prior Market Commentary, which focused on the 2025 equity outlook, raised a few eyebrows and a lot of questions. The eyebrow raise was sticker shock driven, with an out-of-consensus 2025 YE S&P500 bull call of 7434.

The above was premised on a tight labor market leading to economy-wide efficiency gains in the third year of this economic expansion and bull market, leading to a higher earnings growth rate.

This note dives deeper into the productivity rabbit hole, and also explores some the unique macroeconomic conditions of the previous procyclical productivity boom, the 1990’s, to explore how this above average earnings growth rate could come about.

We start with the economic building block of increased returns on capital: productivity.

Higher productivity lowers the inflationary impact of higher nominal growth, leading to higher real inflation-adjusted growth. Higher real growth in turn translates into higher private sector profits and higher living standards for the population at large.

Productivity is what allows for higher nominal wage increases to have a lower inflationary impact, resulting in real higher output.

Higher productivity is what allows for strong nominal growth to not lead to high inflationary growth, resulting in higher real output.

Productivity is what is allowing the post-pandemic recovery to show strong real growth and declining inflation.

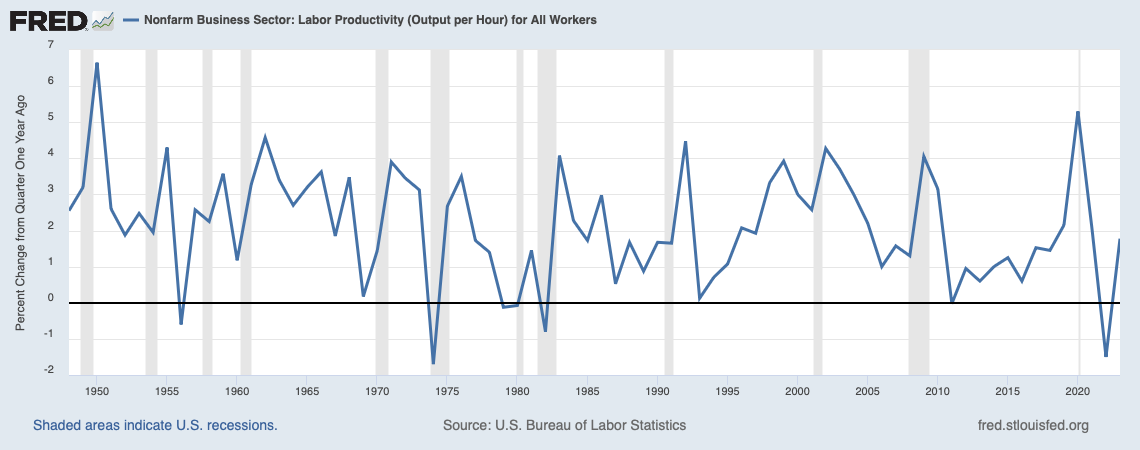

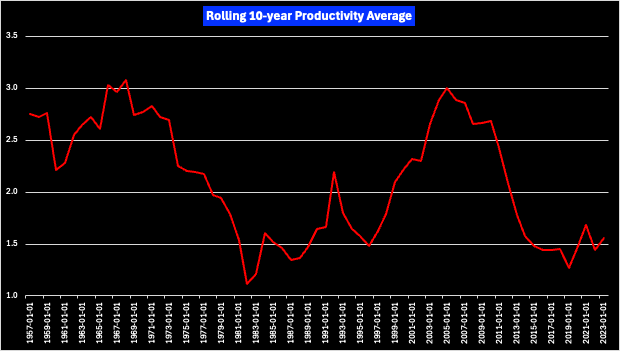

As noted previously, U.S. long run productivity growth has averaged 2.1% since 1948. That number fell to 1.3% in the decade after the global financial crisis.

In the chart below, each discrete point represents a prior 10-year average. Thus, the low point in the early 80’s shows that productivity from 1973 through 1982 was worst in post-war history, and the high point in 2004 represents the high productivity average of the prior decade.

Referring to the first chart, which highlights recession periods in gray, we can see that productivity has historically been counter-cyclical. That is, after a recession hit and resulted in an employment extinction event, productivity shot up in short order.

There is no magic to this, as this was simply an arithmetic response to a realignment of the economy: less workers doing relatively more per worker. As the economy and labor market improved, drawing in more workers into the ranks of the employed, productivity would eventually fall to its pre-recessionary trend as output was marginally lower per additional worker.

The 1990’s bucked this trend, where productivity kept going up from 1993 through 1999.